Meatpaper sEVEN

Leap of Faith

The persistence of pork prohibitions in a swine-centric world

story by Jeffrey Yoskowitz

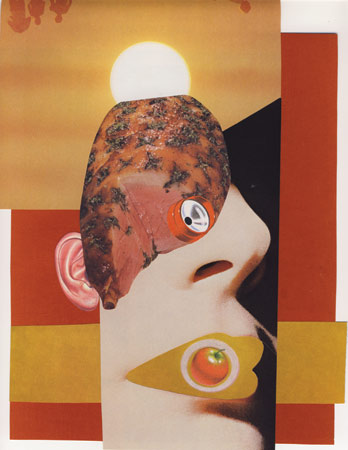

illustration by

Cy de Groat

MARCH, 2009

AS HE RAISED HIS SHARPENED KNIFE to

a chicken in his Queens abattoir, muttering a blessing as

he prepared for the slaughter, Imran Uddin explained to me

the meaning of leading a halal life based on the Quran. “It’s

a discipline,” he said of the Islamic practice, which “dictates

how I speak [and] what I consume.” Then, with one deft motion

he slashed the chicken’s neck. “I wasn’t always halal,” he

added, “but I never ate pork.”

Nor has Chabad Rabbi Mendy Herson ever touched pig meat; he’s spent his entire life strictly following the Jewish laws of Kashrut. “There’s something different about the pig,” he comments with a smirk. “It’s seen as the ultimate isur [sin].”

While their written and oral traditions regarding swine flesh are by no means the same, the age-old pork prohibition plays a major role — sometimes unwittingly — in the lives of Imran Uddin and Rabbi Herson, as it does in the lives of many Muslims and Jews.

After all, both religions subscribe to a belief system that can be alienating, especially when the most commonly eaten animal in the world — accounting for roughly 38 percent of world meat production — is forbidden. When “we create identity markers, we create boundaries,” explains Suffia Uddin, professor of Islamic studies at Connecticut College and sister of Imran. With time and shared experience, “the pig gets further and further magnified in importance,” creating deeply entrenched boundaries.

The pig prohibition has an unusual sticking power. Uddin recounts stories of Muslim friends who would drink alcohol excessively — another forbidden item — but wouldn’t dare touch pork. The same can be said for many Jews. “Many families are not observant, but they hardly ever eat pork,” claims Eli Rosenblatt, a doctoral student in Jewish studies. “It’s a roundabout way of expressing your Judaism, [and] it’s an easy thing to refrain from.”

When I asked Ebrahim — a New Jersey Muslim andlocal Hafiz — to explain the spiritual foundation forthe Muslim pork taboo at the Islamic Center in Basking Ridge, he chuckled and jokingly revealed what seemed like a secret: “The pig is forbidden and [we] have no answer why.”

Rabbi Moses Maimonides, a prominent 12thcentury rabbi and physician in Egypt, pondered this very conundrum. He asked if there was somethinginherently awful about the pig tomake it the subject of such abomination, or if it was merely an arbitrary designation, a test of man’s will.

Maimonides, who lived under Islamic rule and served as a court physician to emperor Saladin, shared his Muslim neighbors’ disgust with swine, according to anthropologist Marvin Harris in his article “The Abominable Pig.” The rabbi had declared that “the principal reason why the law forbids swine-flesh is to be found in the circumstance that its habits and food are very filthy and loathsome,” and pointed to the pig’s proclivity toward eating feces as evidence. It should be noted, though, that Maimonides was unaware that pigs have no sweat glands and thus roll in mud or — in its absence, feces — to cool down.

Today, most Jews and Muslims point to more “scientific” reasons for the prohibition. “It’s because of trichinosis,” respond countless young Jews in New York when asked about why the pig is forbidden. Ebrahim mentions, “Doctors say pigs do bad stuff to the brain.” Ali, the head of the Basking Ridge Muslim community, explains, “Even if you cook it thoroughly, you can still get parasites and get brain disease.” The general health of wayward Muslims and Jews who have abandoned the religious code may discount some of those claims, though the guilt ... well, the guilt is the subject of almost every Woody Allen film and Jewish joke. And as Suffia Uddin suggests, some Muslims will eat differently in the presence of other Muslims than when they’re alone because of shame.

Anthropologist Marvin Harris has worked to debunk many of the popular scientific explanations for the pork prohibition. “If the taboo on pork was a divinely inspired health ordinance,” he writes, “it is the oldest recorded case of medical malpractice.” Harris believes that the pig was forbidden in the Torah and the Quran because the cultures knew that raising pigs in the desert climate was imprudent. Ruminants such as goats and sheep can transform grass and shrubbery into fat, but pigs, omnivores with the same digestive structure as humans,need to eat the same foods as humans.

Nevertheless, many Muslims share Maimonides’ disgust with pigs. Imran’s father calls them the “filth of the earth,” then gets angry at the very thought of one. Many Muslims believe that the habits of these animals are transferable through ingestion, which would make one who eats a pig “shameless” and “self-centered.” That’s why Imran thinks Muslims should be more like lambs, who are “communal creatures, gentle and clean.”

Ultimately, however, the taboo doesn’t need to be rationalized, because in the case of both religions, the pig has been banned in scripture — in surprisingly little detail. The Quran states in Sura 42:14, “Don’t eat pork to be righteous,” and in Sura 5:3, “Prohibited for you is the meat of the pig.” The Torah tackles the issue twice, in both Leviticus and Deuteronomy, proscribing the eating of swine because they have cloven hoofs but do not chew their cud.

However, the true sticking power of the pork prohibition lies not just in the letter of the law but in how, as Suffia Uddin describes, the markers of identity apply, both for those on the inside as well as those on the outside.

And for nonbelievers, the pork prohibition is one of the most well-known practices for Jews and Muslims, which is why it has been included in the history of oppression. Legal scholar Daphne Barak-Erez argues that “abhorrence of pigs is a constitutive foundation of collective Jewish memory.” In the events of Hanukkah the Greeks invaded Judea and passed edicts mandating that priests “sacrifice swine and eat ritually unfit animals (1 Maccabees 1:1).” They even forced Jews to eat pigs in the streets. Famed cultural anthropologist Mary Douglas claims that the Greek ruler Antiochus turned not eating pig into a symbol of “cultural allegiance.”

The pig has been a part of more recent struggles of assimilation. Xenophobes have thrown pig heads into mosques in Europe and have stuck pig heads on stakes outside of Muslim schools in Australia; and in November 2008, German neo-Nazis placed a sign with an image of a pig’s head on a Star of David outside a cemetery, reading “six million lies.” And while secularizing forces of globalization have led to western assimilation in the Muslim world and in Israel, governments have attempted to enforce the prohibition. In Turkey, the pro-Islamic government is trying to shut down the once-thriving pork industry, and the ultra-Orthodox Jews in Israel are fighting to ban the sale of pork in their towns. Meanwhile, Qatar television has censored the image of Piglet in its broadcasting of Winnie the Pooh. The old joke that apparently the only two issues that can bring Orthodox Jews and fundamentalist Muslims together in agreement are those of gay rights and pork begins to ring true.

For Muslims and Jews trying to assimilate in the Christian West, pork can prove to be an obstacle. The mell of bacon can be a source of nausea for some. Ali confessed, “I don’t feel comfortable when I smell bacon being cooked. That’s ingrained in you when you grow up with it.” There is an unwritten ritual of pestering waiters with detailed questions about how meals are prepared. Imran’s father, for instance, usually tours the facility, and if the kitchen does not serve pork, he’ll have the fish. If there’s pig on the menu, he’ll take a salad.

An entire food industry worth billions of dollars has sprouted to accommodate the needs of these two groups. Kosher certifications on food products ranging from canned soup to aluminum foil certify that no non-kosher animal by-products were used in production. Similar halal certifications exist, and organizations in both communities circulate lists explaining which products are free of pig fats and which once-favored products are now tragically being produced with gelatin or other pork derivatives.

The kosher meat industry has come under fire quite recently because of scandalous behavior— substandard wages, illegal alien workers, etc. — that have been revealed at Agriprocessors in Postville, Iowa, the largest kosher meat plant in the United States until its bankruptcy in 2008. In response, Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld wrote in the New York Times, “This poses a grave problem and calls into question whether the food processed in the plant qualifies as kosher.” Now a whole new generation of Jews is approaching kosher meat with issues of ecological sustainability and ethics in mind. Imran shares similar concerns and recognizes the same sentiment percolating in the American Muslim community, which is why his animals are from farms he knows and trusts and are only caged right before slaughter. He’ll soon begin selling whole chickens in supermarkets on biodegradable cornstarch trays.

Given all the uncertainties in adapting ancient dietary codes to modern, industrial standards, the pork taboo offers a unique simplicity that explains its lasting significance; there are no complicated questions of slaughter, or what blessings to say, or what happens if workers are not paid proper wages. Rather, while a globalizing world works to dilute and shed cultural traditions, the pork prohibition offers proof that shrinking cultural divides don’t always erase traditions, but sometimes test their strength.

JEFFREY YOSKOWITZ is a food, environment and culture writer based in Brooklyn. He spent 200-2008 living in Israel documenting the country's pork industry, and has yet to stop thinking about pigs. He loves meat but eats it selectively, and prefers the kosher, natural and ethical variety.

CY de GROAT is a collagist who lives and works in a tree house in San Francisco. Cy's curioustiy about pigs began during a childhood visit to the zoo where she saw a piglet who shared her name. Despite the fact that this led to years of being tortured by her family, Cy continues to feel a strong affinity towards pigs.

This article originally appeared in

Meatpaper Issue Seven.

|