Meatpaper TWELVE

The Afterlife of Afterbirth

Notes on eating human placenta

story by Cynthia Mitchell

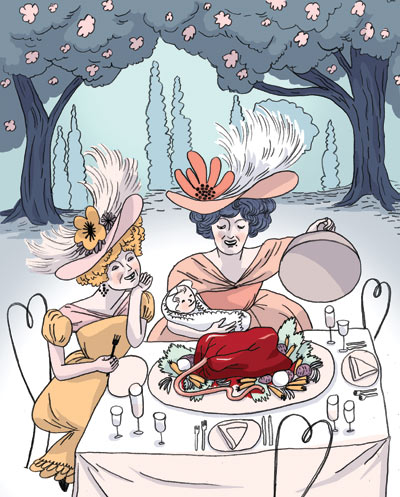

illustration by Emily L. Eibel

June, 2010

A COUPLE OF MONTHS AGO, my roommate asked

me if we could host a placenta dinner.

A San Francisco–based group called Adventures in Dining had

a placenta donor (an anonymous one; I never learned her name)

and needed a location for their adventure.

I said yes. How

could I not? Admittedly, I was more intrigued by the mise

en scène than by the primary ingredient of the proposed meal.

What types of people attend placenta dinners? Is it a somber

occasion? Formal? I imagined women in long gowns, chic yet

ceremonial, sipping wine and murmuring quietly about their

mysteries. I thought it would be magic without being dorky,

something a style magazine might call “metro-Wiccan.”

All mammals except camels and kangaroos

eat their placentas, which made me think ancient

humans probably did, too.

The

dinner was canceled. We were told, rather cryptically, that

the designated placenta had been tainted with formaldehyde.

I suspected a hospital worker — someone unaccustomed to women

wanting their placenta food grade. I knew a kid in high school

who smoked formaldehyde for its PCP-like effect. The thought

of ladies smoking placenta and moonwalking around my living

room was oddly appealing, but getting high was not the point.

Once I realized my curiosity over the nature

of placenta diners would not be satisfied, it struck me that

I didn’t really know what a placenta was. I’d imagined some

kind of moist, translucent fetus wrapper. When I saw a photo

of one, I was shocked. A placenta is a huge thing, one-sixth

the size of a newborn, and it looks like a handbag made of

blood. In case I’m not the only one unfamiliar with procreative

miracles, a placenta is an organ that grows inside a woman,

connecting the fetus to her uterine wall and allowing the

developing creature to feed and eliminate waste through the

mother’s bloodstream. That may seem obvious and natural,

but I can’t help feeling that it’s weird to suddenly grow

a disposable organ in which to keep a person you’ve never

met.

In the United States, placentas are typically

treated as medical waste. Some hospitals hold them for a

couple of days, but most throw them out immediately, which

struck me as a reasonable thing to do with a used sack of

blood. Then I began to read about people around the world

who believe these organs contain powerful, protective, and

sometimes dangerous spirits. That we throw such organs in

the garbage along with hypodermic needles, cheek swabs, and

tongue depressors was starting to seem sad and lame. After

all, placentas have been eaten; buried; burned; marched in

parades; sung to; dressed in clothing; entombed in pyramids

(of their own!); floated down rivers; stolen; sold; used

to curse, bless, cure, and beautify; been talked to; not

talked in front of; taken on trips; given gifts of pens and

needles; taken to school; fed; stabbed; used to make art

prints; turned into teddy bears; tied to the heads of children;

and probably a host of other things too strange or mundane

to record.

Plus, all mammals except camels and kangaroos

eat their placentas, which made me think ancient humans probably

did, too.

In

Deuteronomy, God threatens the Israelites for 54 chapters.

He says a woman “will begrudge the husband she loves and

her own son or daughter the afterbirth from her womb and

the children she bears. For she intends to eat them secretly

during the siege and in the distress that your enemy will

inflict on you in your cities.”

The Compendium of Materia

Medica, a tome by the famous 16th-century Chinese physician

and pharmacologist Li Shih Chen, recommended a mixture of

human milk and placenta as a treatment for chi exhaustion,

a condition characterized by cold sexual organs and premature

ejaculation.

Despite these examples and claims on numerous

maternity websites that placenta eating is an ancient custom,

there is little documented evidence of what doctors and academics

call “placentophagy” until the mid-19th century, according

to Dr. William B. Ober, author of Notes on Placentophagy.

After that, anthropologists, doctors and nurses, missionaries,

and writers noted a long list of cultures ingesting placenta.

Placentas have been eaten, buried, burned,

marched in parades, sung to, dressed in clothing, entombed

in pyramids, floated down rivers, and probably a host of

other things too strange or mundane to record.

The Kurtachi of the

Solomon Islands preserved placenta in a pot with lime powder

to flavor areca nuts. In Jamaica, placenta tea was given

to infants who were being bothered by ghosts. In Peru, chewing

the umbilical was said to prevent illness. The Araucanian

Indians of Argentina gave it in a powdered form to sick children.

The Chaga of Tanzania dried it for two months and then ground

it with plants to be eaten by the child’s elderly female

relatives as porridge. The Kol tribe in central India believed

that if an infertile woman stole a placenta and ate it, she

would become fertile, but an injury would occur in the family

from which it was taken. In Hungary, women tired of childbearing

would burn it and secretly feed the ashes to their husbands.

In Java, Moravia, and Morocco, placenta was eaten to increase

fertility. The Chinese used placenta to hasten labor. In

Italy, it was thought to induce women’s milk flow and reduce

pain. Austrians considered it a cure for epilepsy and sold

it in pharmacies. In the 1960s, Czechoslovakian nurses reported

that Vietnamese immigrants ate placentas fried with onions

after giving birth. In Romania, eating it was said to keep

away the cold. And Germans reportedly mixed placenta with

butter.

In 1983, Mothering Magazine published a

series of placenta recipes, including ground placenta pizza.

Right now, women are eating their placentas in YouTube videos

of home births. Even vegans eat it, though not without some

controversy.

A surprising number of modern women and

even a few men espouse the benefits of placenta eating. In

2006, Tom Cruise told Diane Sawyer that he was planning to

eat Katie Holmes’ placenta. Placenta-loving websites like

momlogic.com and placentabenefits.com will tell you that

placenta contains oxytocin, a hormone associated with pain

relief, orgasm, pair bonding, and relaxation, sometimes called

the “cuddle hormone.” Placenta is also said to contain progesterone

and vitamin B6. It is believed to be good for preventing

postpartum depression, stimulating milk flow, repairing the

uterus, stopping hemorrhaging, and getting silkier hair.

All these online testimonials made eating placenta seem like

downright sensible nutrition. But I had yet to hear a first-person

account from someone who’d eaten it.

Figuring the modern

incarnation of this practice must have caught on in the 1970s,

I called Jacqueline Darrigrand of San Francisco, a self-described

feminist who wrote her master’s thesis on witches, did a

back-to-the-land stint, and doesn’t flinch at organ meats.

“Hi

Mom. Did you or any of your friends eat placenta?”

“What?

I’m walking down the street. I can’t hear you very well.”

“PLA-CEN-TA.

Did anyone you know eat placenta?”

“Oh! Ha! No one I know

did it, but I heard about it happening. It’s supposed to

be very nutritious.”

“Did you want to eat our placentas?”

“I can’t say that I was

tempted, no. Anyway, I don’t think that was offered to me

as an option.”

“Do you think it’s gross?”

“Nothing is grosser than giving

birth.”

I called Sean Uyehara, a San Francisco

film programmer whom I knew had a child.

“Did you eat your

kid’s placenta?”

“No. The hospital kept it. I think they

ate it themselves.”

“You think they made Jell-O?”

“Probably

some kind of headcheese.”

Finally, I was given the phone number

for a known placenta eater. When I talked to Kim, a professional

photographer from Massachusetts, she sounded personable,

open, and humorous, not really my idea of an auto-cannibalizing

pagan. She said that after giving birth, she had lost a lot

of blood and was feeling weak. Her midwife asked if she would

like to eat some placenta. She agreed, and her midwife sautéed

it and served it on a plate with onions and eggs. “At the

time, I was kind of delirious from blood loss and delivery,”

she said. “Mostly I look back and am grateful for how it

made me feel after a hard labor and how surprisingly normal

it felt.” Of the flavor, she said only that it was “not strong.”

Paul

Reller, an acupuncturist in San Francisco, told me that he

ate placenta while in acupuncture school. “A lot of the other

students were freaked out, but I ate some,” he said. “It

was dried and shaped like a little flat cookie. It was extremely

tasty, sort of sweet.”

I heard that Christina Buckingham,

a performance artist sometimes known as “Chaos Kitty,” had

eaten hers, so I called her too.

“Hi, I know we haven’t talked

for a while, but I have kind of a funny question. Did you

eat your placenta?”

“I was going to, but I got too grossed

out. I think maybe I overcooked it. I slow-cooked it all

day and the smell was nauseating.”

“What was the smell?”

“Like old yak meat,

kind of gamey. I think maybe I shouldn’t have frozen it first.”

“Who

were you going to feed it to? Were you going to have a dinner?”

“I

wanted to feed it to my husband, but he wasn’t interested.

It’s hard to do things like that when you have a cynical

husband.”

In the background, I heard the high-pitched

voice of a toddler and then my friend saying, “I wasn’t going

to eat you! I might eat you now, though!” Then a little voice

laughing, “But I’m full of bones!”

From what I could gather,

making a tasty placenta dish is not easy. The recipes I found

online and in books were mostly Italian-American family dishes

like lasagna, calzones, and spaghetti. To my mind, cooking

placenta in a sloppy red sauce and adding cheese does not make it more appetizing. Here’s an example of a placenta

lasagna recipe, this one I copied from a website called mothers35plus.com:

1 fresh, ground, or minced placenta

2 tablespoons olive oil

2 sliced cloves garlic

1/2 teaspoon oregano

1/2 diced onion

2 tablespoons tomato paste, or 1 whole tomato

Use a recipe for lasagna and substitute this mixture for

one layer of cheese. Quickly sauté all the ingredients

in olive oil. Serve. Enjoy!

Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, a chef from

the U.K., scandalized the country in 1998 by making placenta

pâté and serving it on his TV show Cook on the Wild Side.

According to BBC News, the placenta donor’s husband had 17

helpings but the other guests were less enthusiastic.

The

descriptions I read and heard of placenta’s taste were wildly

diverse, everything from sweet to salty, like liver, not

like liver, like filet mignon, textured like heart but more

spongy, like offal, like eating a plateful of garden earth.

Even

though I never got the opportunity to host a placenta dinner,

all this talk of flavors and organ meat had me wondering

about an appropriate wine pairing. I asked Gus Vahlkamp,

sommelier for the Slanted Door, a renowned restaurant in

San Francisco known for its iconoclastic wine list. He responded

in an email:

“After a couple of conversations with my

peers (and people who have handled placenta, though never

eaten it), we think the best all-around recommendation would

be a red wine with minimal oak, high acidity and pronounced

mineral overtones, rather than ripe, primary fruit flavors.

If we were going for complementary pairing, the best choice

I think would be a wine made from mencía, a grape variety

indigenous to northwestern Spain; mencía is vinified in many

different styles, but the best ones for our purposes come

from Bierzo, where the wines are known for their earthy,

sauvage notes and fairly rugged character. Jon Bonne from

the San Francisco Chronicle has written that these wines

actually remind him of blood.”

CYNTHIA

MITCHELL makes

moving pictures, still pictures, and pictures with words. She

lives in San Francisco.

This article originally appeared

in Meatpaper Issue Twelve.

|